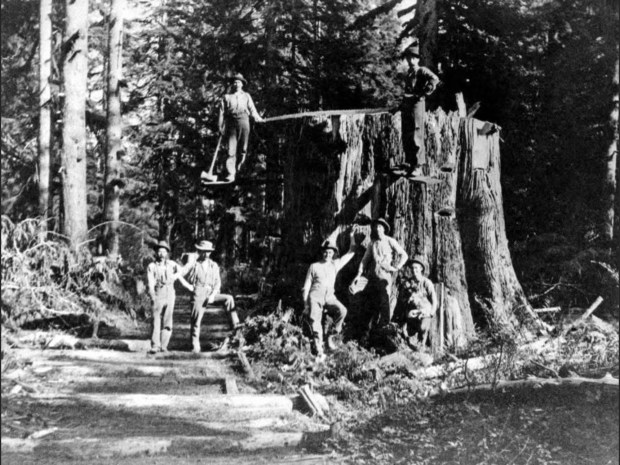

Sometime, over 100 years ago, we logged North Burnaby and took out centuries old giants like this. We don’t know what we’ve lost, because it was gone before we were born. But, not that long ago, this was a magnificant old growth forest.

Crabtown 1912 to 1957

One hundred and twenty five years ago, Burnaby was wilderness with a dollar sign attached to it. There was a lot of old growth timber that was being logged, forest to be cleared, fish to be caught and crabs to be harvested.

Like most frontier towns, rules were few and dollars were scarce. People started building squatters homes on the North facing shore of the Burrard Inlet, where Burnaby Heights now exists.

Poor workers from the mills and other basic industries like logging and fishing started building these squatters homes in around 1912. It’s not hard to figure out why it was called Crabtown. People are still pulling thousands of crabs from the waters east of the Ironworkers’ Bridge.

An entire generation was born and raised in this community, which exhibited the pioneer spirit of invention born of necessity. Lumber was plentiful, food was there for the catching. As with most such spontaneous, unregulated communities it developed largely unnoticed and tolerated and grew to about 114 homes and 130 residents.

Then in 1957, the federal government, concerned about the encroachment on federal lands, evicted all 130 residents and tore down the homes. I suppose that was inevitable, as Burnaby was growing and regulations were put in place.

How did building mansions turn into building a refinery?

This is a photo of Overlynn mansion which can be found at the corner of Trinity Street and North Edmonds Avenue in the Heights. Below that is a view of the tank farm in the Heights.

Designed by the premier architect of the time, Samuel Maclure, Overlynn was built in 1909 for Charles J. Peter. Peter felt that the Vancouver Heights area was one of the most picturesque in the Vancouver region. It was named because it overlooked Lynn Valley to the north.

Peter was the head of the Blue Ribbon Tea Company and he was promoting the area as the next Shaughnessy.

According to some research, the average home in the Vancouver area at that time, was $1,000. Homes in Vancouver Heights were selling for $3,500.

Overlynn reportedly cost $75,000!

If you wander through the streets of Northwest Burnaby, you will find a handful of these old mansions, built over a twenty year period from 1909 to 1929. It was believed the Heights was the next big thing.

Aside – at some point between 1980s and now, Vancouver Heights was notionally split into two sections – the Vancouver side of Boundary, north of Hastings and East of the PNE is referred to as Vancouver Heights and the area east of Boundary, north of Hastings and west of Willingdon is considered Burnaby Heights. More recently, it is now referred to as the Heights.

Certainly, after all the old growth forest was logged, the views were (and are) spectacular.

So, what happened? You saw that part where I said the original building took place in a period ending in 1929. We all know what happened then. A great stock market crash, an agricultural crisis and a global trade war initiated by the Smoot Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, enacted by the USA to protect American business and farmers. You’d almost believe that people didn’t learn the lessons of history!

So, a lot of wealth disappeared as a result of the crash, which led to the Great Depression of the 1930s. Not a lot of mansions get built in a frontier town like Burnaby during a depression but a lot of jobs were lost. So, when Standard Oil proposed building a refinery on the waterfront of the Heights, the prospect of jobs was too enticing and a Faustian bargain was made. Ninety years later, we are still living with a major industrial site on some of the most valuable and picturesque real estate in Canada.

Imagine a world where, instead of a tank farm, we had a gently sloping public park that stretched to the waterfront beach, with a public pier and natural habitat. Instead of a refinery, there was a marina and more natural habitat.

We can dream, can’t we?

This is the Burnaby section of the Trans Canada Trail that goes through McGill Park in the Heights. It skirts along the Parkland Tank Farm. But it wasn’t always there. In the early ’90s, Chevron owned the Refinery and tank farm. They announced that they were going to expand the boundary of the tank farm to include most of what you see in these photos to make a bigger parking lot.

I called their office and got a visit from their environmental manager, who offered to take me to the site where they were going to build their new parking area. He pointed out this area and said “That’s where the parking lot is going.” I asked him “How do you think your neighbours will feel about turning this green space into a parking lot and fencing it off?”

He said “It doesn’t matter, we own this land.”

Wrong answer! I went back home, told my wife Angela what transpired and we got busy. Within a few days, we formed a neighbourhood group to oppose this. We called it Burnaby Residents Against Chevron’s Expansion (BRACE).

We got a lot of publicity and Chevron decided to back down. So, instead of a parking lot, we have the Trans Canada Trail.

There were many other benefits that accrued to the neighbourhood as a result of residents pushing back and asking questions. A Community Advisory Panel was formed and more than 30 years later, it’s still going. Pollution monitors were placed in the buffer zone. Most importantly, we got them to put a vapour recovery system in place at the marine loading facility and it greatly improved the air quality.

Now, it’s time to move to the next phase of converting part of the buffer zone into habitat that supports biodiversity.

So, after the old growth forest was logged, houses, roads and businesses were built, the refinery moved in, people settled into suburban life in North Burnaby. It was originally a working class neighbourhood back when blue collar workers, teachers and small business owners could afford to buy a modest home. The housing changed throughout the 20th century from 1 and 1/2 or 2 storey wood sided homes built in the ‘teens, to some arts and crafts style homes in the ’20s and ’30s and the post WWII bungalows built in the ’50s and ’60s. In the ’70s, the Vancouver Specials began being built and so on until today, with the 3.5 million dollar large homes being built.

During this period, nature was either something to be exploited, removed, or poisoned. Most natural habitat was lost. In the few areas that weren’t developed after they were logged or drained, nature has tried to stage a comeback. But into the void that was created, plants from residents’ gardens, found their way into the recovering natural areas. Plants like English Ivy, blackberry, holly trees, laurel, or morning glory found lots of space and no natural checks and invaded with alarming results. These are the plants in the accompanying photos (along with some ancient trash).

Since we didn’t know what was originally here (because it was gone before anyone currently living was born), we didn’t realize the insidious creep of invasive species. They covered the forest floor, crowding out the native plants that should have found space to grow. Those native plants supported insects – native beetles, bees and butterflies, so their absence had a rippling effect in the great web of life. Fewer bees meant fewer native plants were pollinated. Fewer butterflies meant fewer baby birds, whose diets are 83% caterpillars. And so on, up the chain.

It took decades for these invasive plants to become established to the point where people started noticing. I moved here 50 years ago from Alberta and, to me, it was a verdant natural environment. I didn’t know that holly trees were not native. Or that ivy hadn’t always smothered the forest floor. It wasn’t until I retired and had the time to pay attention to what was going on in the woods as I walked to the Trans Canada Trail that I realized there was trouble in paradise. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

So, we (WONS) are embarked on what will be an inter-generational rehabilitation of our urban environment to, once again, accommodate the natural world. So, if you’re a gardener, a birder, a nature lover – join us as we work to protect and promote biodiversity. The world will be a better place for your efforts.